BNP Paribas in China: more than 160 years ago (1/5)

Long before it established its countrywide network in France, the Comptoir d’Escompte de Paris (CEP) opened an office in China. For more than a century and a half, the various banks that preceded the Group were able to cope with the tribulations that punctuated modern history in China. But their presence, in various forms, also demonstrated that they understood the country’s enormous potential and were able to build lasting economic and financial relationships.

The period 1860-1880: early growth in China with the Comptoir d’Escompte de Paris

When China opened its doors to Western countries, Comptoir d’Escompte de Paris (CEP) seized the opportunity to establish its first two offices in China in 1860 in order to support its national economy and promote diplomatic ties between France and China.

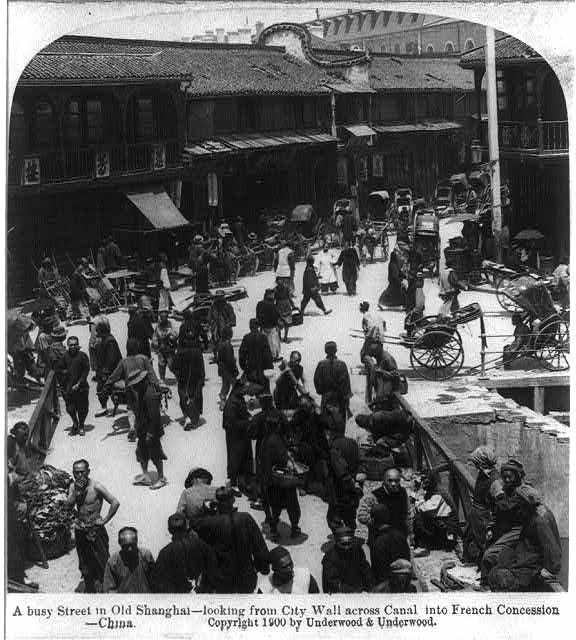

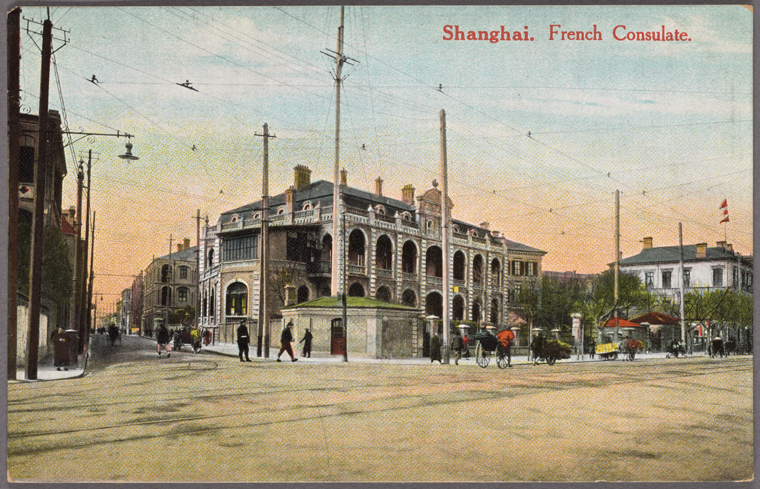

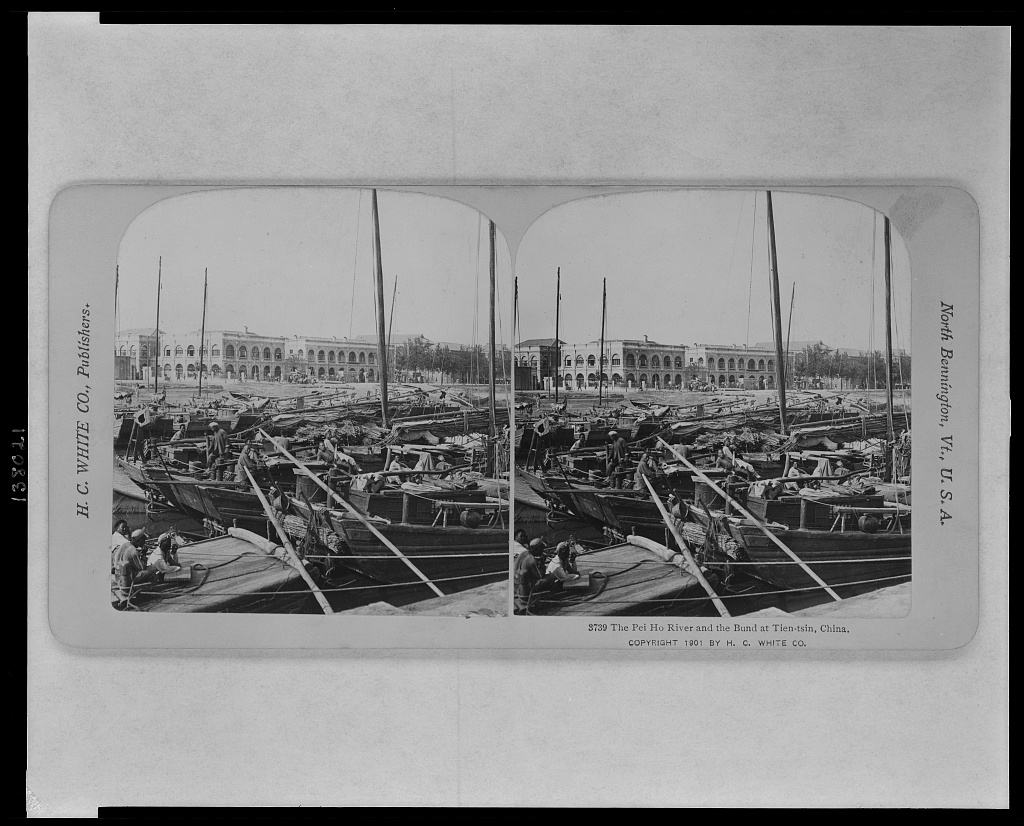

France’s interest in China goes back a long way. The First Opium War between England and China from 1840 to 1842 marked the start of Western penetration and forced China to sign concessions to the British, followed by the French: the opening of 5 French trade harbours (Canton, Shanghai, Amoy, Fou Tcheou and Ningbo), and the right for foreigners to stay there, trade directly with the Chinese, or set up a consulate. From 1860, 11 new harbours became accessible to foreigners. The concession system spread to large cities such as Shanghai, where a British concession was established in 1845, followed by a French one in 1849. Canton, Tientsin, Hankou, Amoy and Fou Tcheou in turn received concessions from 1860 onward. The Middle Kingdom thus ceased to be the inaccessible fortress which twenty years earlier had no contact with the outside world.

At the same time, the signing of a free-trade treaty with Great Britain in 1860 would facilitate the roll out of large retail for France in the British Empire. In the same year, by decree of 25 May, Comptoir d’Escompte de Paris (CEP) obtained permission to establish offices in French colonies and abroad. Having specialised up till then in discounting (escompte), it opted for a new growth strategy and decided to support trading in all its transactions, by broadening the scope and regions of its business. To meet the demands of its customers who lived abroad and wanted the support of their bank, CEP decided to open agencies overseas, and thus became the only establishment to organise the financing of French international trade in the countries of production.

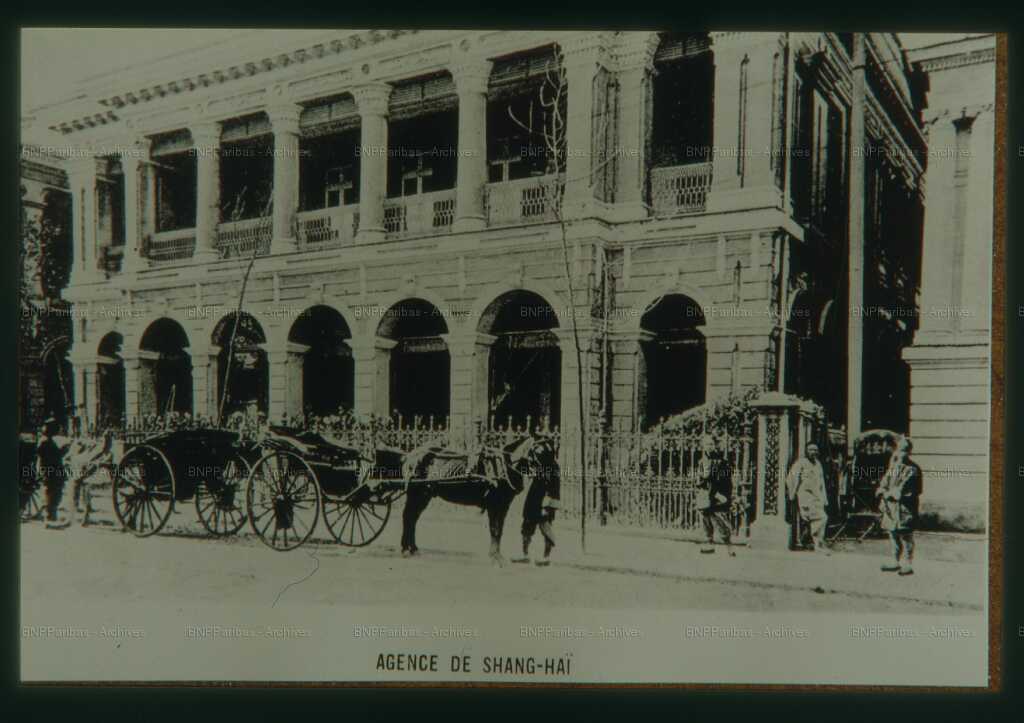

China was the first country where the Comptoir opened an agency: Shanghai was the first milestone in 1860, followed by Hong Kong in 1862. The French business world first became interested in China in the 1850s.

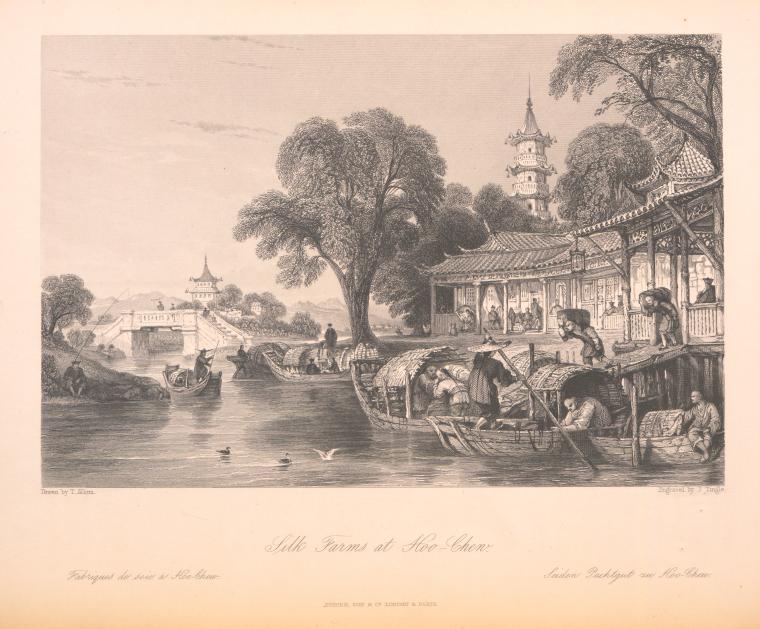

Lyon manufacturers were the most active, with silk imported from Canton, Shanghai and Hong Kong allowing them to replace the European and Mediterranean production that had suffered from a pepper disease epidemic in 1851. At that time, European industry was looking for large quantities of commodities and also hoped to find bigger market opportunities. Chinese business growth prospects were looking promising.

Becoming operational in September that year, the Shanghai office acted as intermediary in the collection of war indemnities owed to France by the Chinese government after its defeat in the Second Opium War (1856-1860). It equally contributed to the development of direct silk and tea imports from China to France, as well as the export of manufactured goods from France. By 1865, five French companies were already established in Shanghai. Modest at first, silk trade in the Far East would by the start of the 1880s represent a third of all silks regardless of origin.

In 1884, the Lyon Chamber of Commerce commissioned Paul Brunat, an engineer who was an expert in the silk industry as well as the Far East, to investigate trade prospects in the region known as “the new Asian colony”.

In 1885, the “French industry mission in China”, created under the aegis of CEP, benefited from the position acquired through warfare to look at possibilities to undertake large civil engineering projects. Following a positive outcome, the Comptoir, which had become the “French Bank” in the Far East, opened branches and sub-branches in Tientsin, Fou Tcheou and Hankou in 1886. The desire to combine the development of a sphere of influence and railway concessions, major works contracts and loans, proved that the two French business drivers in China – Foreign Affairs and the financial world – mutually supported each other: French diplomats, traders, industrials and bankers joined forces to expand their influence in China and obtain as many concessions as they could. Let us not forget that in the 19th century, the banking system in Asia was dominated by British and Japanese banks. There was undeniably a clearly stated desire to compete with British banks and businesses on their own turf.

CEP was a trailblazer in Asia, as its competitors until then had preferred to work with corresponding establishments when setting up their business abroad. But its results in China during those years were mitigated. Its presence was disturbed by the eventful history of China, leading to the successive opening and closing of offices at the end of the 1870s and in the 1880s, which would cause it to reconsider its strategy in China and in the region as a whole.